A grotesque Man of Sorrows

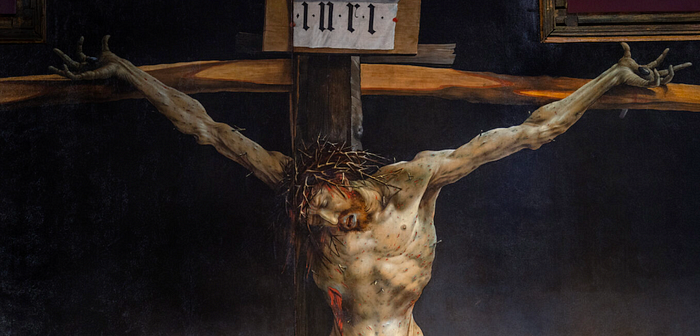

A monstrously violent execution in the middle of the night: a thin, gaunt man, his skin a sickly gray-green and pockmarked with the scars of pox, hangs from a cross, his limbs contorted and hands outstretched in agony. Blood runs from his freshly pierced wounds, dripping down from his ribs and feet. His mouth wails silently in unimaginably painful death; the crown of thorns angrily juts into his skin like the splinters upon his body. His grieving disciples surround him; there is no peaceful, merciful death here, no ecstatic revelation. There is only the dark bleakness of suffering and death.

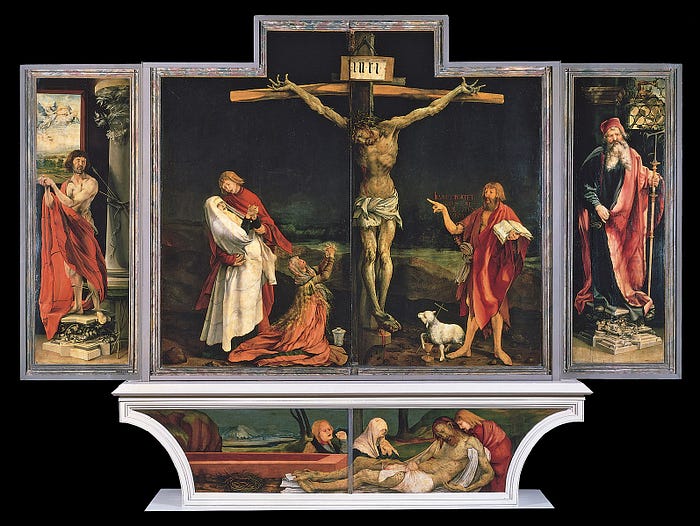

This is Matthias Grünewald’s monumental Isenheim Altarpiece, one of the most bleak and solemn, and simultaneously one of the most fantastic and magnificent, works of the North Renaissance tradition. A massive piece, measuring over 12 feet by 22, it functions as “essentially a box of statues covered by folding wings” (Hickson); three sets of wings of painted panel swing outwards to reveal Biblical scenes that ultimately lead to a polychrome wood ensemble of three seated saints, a multimedia type of altar popular in Germany at the time. (A video of the full altarpiece being opened can be seen here.)

This article will only analyze part of the Isenheim Altarpiece, which consists of six hinged wings, ten individual painted scenes, and sixteen polychrome wooden sculptures. Specifically, we will be looking at arguably the most intriguing—and disturbing—part of the altarpiece: the crucifixion scene, the very first motif the viewer sees when it is fully closed, as it usually was in its original setting. This violent depiction and its meaning go far beyond the mere vehicle of corporal suffering; rather, they both serve to emphasize the overarching meaning of the work itself, not one of despair, but one of comfort and hope.

A hospital for the dead

When analyzing any work of art, careful observation and consideration of its original setting and function are paramount to fully understanding the work. The Isenheim Altarpiece is no exception to this rule; indeed, a full grasp of its original context is vital to understanding Grünewald’s meaning completely.

This monumental work was originally “created to serve as the central object of devotion in an Isenheim hospital built by the Brothers of St. Anthony” (Hickson). Such altarpieces, serving as focal points serving as objects of devotion and hope, were not uncommon in European hospitals of the time, many of which were run by monastic orders such as the Hospital Brothers of St. Anthony.

We must note here that this hospital was not necessarily a place of healing and wellness; on the contrary, many patients here were probably beyond the point of saving and were at the point of succumbing to their illnesses. A better name for it would be hospice care, for that was what the monks of St. Anthony mostly attended to. This was not a place for actively getting better and recovering from sickness; rather, this was a place for comforting those who were about to pass away, treating them with care and compassion while offering them hope for a better life after this one.

As Professor Andrée Hayum notes:

“Present-day medical attitudes and treatments are primarily geared toward preservation of life… This situation is in sharp contrast to that of the early sixteenth century, when diseases quickly took on epidemic proportions… Hence the practice of medicine then was.. alleviating illness rather than restoring health” (Hayum).

This is especially true given the fact that many of the patients there suffered from ergotism, a deadly disease that came from consuming rye bread infected with fungus. It was also, incidentally, called St. Anthony’s Fire. The diagnosis was generally grim: patients could get painful seizures and convulsions, often leading to psychosis or mania, within hours of eating the contaminated food. Even worse, patients could become infected with gangrene, dying painful deaths of detached fingers and/or entire limbs. Ergotic patients would be stricken with characteristically pockmarked skin, which would cause painful scratching. The chances of survival were slim, especially after monks would often unwittingly feed patients infected bread.

Ergotism was a notoriously terrifying disease, claiming many thousands throughout the centuries of European history. Perhaps the most viscerally horrifying description of this disease comes from 11th-century monk Sigbert von Gembloux, who named 1089 the “Year of the Plague”, writing:

“That year there was an epidemic, where the Holy Fire consumed the innards of many people, who simply rotted away, because their limbs became black as coal and were eaten away. They either died in anguish, or their hands and feet fell off and they wasted away, living a painful life. Many people suffered, tormented by cramps, a real torture” (Stieglitz).

In a place of such grievous suffering and pain, the Isenheim Altarpiece stood as a central visual attractor in the space and the primary focal point of the patients. Its wings were closed most of the time, which meant that the patients would see the scenes of the crucifixion and deposition in the closed frontal state of the altarpiece most often. Only on specially designated feast days would the wings of the piece stretch open, revealing a vibrant and colorful interior.

The context of the Isenheim Altarpiece, then, was grim, painful, and tragic. Disease was a part of life in its original place; death was, of course, common. Keep this in mind as we begin to analyze the form and content of the work itself.

The marred crucifixion

Like a twisted kind of visual magnet, the central theme of the crucifixion invariably draws our eyes toward the suffering, bloodied body of Christ. And how could such brutal visual agony not command our attention?

Indeed, the more one gazes at the central crucifixion panels, the more one feels disturbed, almost revolted, at the sheer scale of agony and suffering depicted so eloquently in the form of the crucified Christ. His limbs and hands stretch out and contort in obvious pain. The scarlet blood running from his stigmata contrasts so clearly with the pale skin of recent death, marred by splinters and—crucially—the characteristic pockmarks of ergotism.

This emphasis on connection with the ergotism of the patients of the hospital is further reflected in the body of Christ, which is depicted lying in the predella of the altarpiece. Christ’s corpse sprawls across the panels, bleeding and horrifyingly punctured. And, of course, the ergotic pockmarks are present here as well. The choosing of the two saints who flank the central panels, too, is no mere coincidence; Saint Sebastian was venerated as a patron of plague victims and a protector against bubonic plague (due to his body being marked with arrows), while Saint Anthony the Great was the namesake of the monks who cared for the sick here.

Several characteristics of Grünewald’s central panels are especially noteworthy. The lack of the halo in the forms of both Christ and the Mater Dolorosa, as well as in the forms of the flanking Saints Sebastian and Anthony the Great, speaks to the decline of the overt use of the “Byzantine” halo during the Renaissance. And, of course, the motif of the crucifixion with the Mater Dolorosa and the Agnus Dei is everything but new in the tradition of Western Christian art.

Many visual characteristics and nuances, however, stand out from this tradition. Consider the setting of the crucifixion; the sky is darkened (perhaps not a nighttime scene, but rather a nod to the eclipsing of the sun recorded in the account of the crucifixion within the Gospels), and the distant landscape undetailed, so that a black curtain seems to fall behind the action. John the Baptist, usually reserved for other artistic motifs, is included standing by the cross. And, of course, the form of Christ is contorted in pain; his suffering is dialed up to the point of near-grotesque abstraction.

The significance of pain is crucial to this work; as Professor Hayum writes,

“Pain is essentially a private experience that isolates its victim from his surroundings. In the open stage of the Isenheim Altarpiece… Grünewald seems to urge the viewer’s confrontation with this immediate reality, and he presents a circumscribed possibility for its alleviation” (Hayum).

Such artistic choices stand in stark contrast to the depictions of the crucifixion in different parts of Europe during the Renaissance, most specifically in the South (think Italian city-states here), where the humanistic emphasis was on mathematical perspective, realistic atmospheric landscapes, and stability. In Mantegna’s The Crucifixion, for instance, we find an entirely different scene from Grünewald’s panels, though the subject matter is the same. Mantegna’s Christ is almost pensive and restful, his halo glowing; Grünewald’s Christ is contorted in palpable agony and sans halo. Mantegna is interested in depicting atmospheric and mathematical perspectives; Grünewald’s background is almost pulled forward in its simplicity. Mantegna’s sky is blue and light; Grünewald’s is blackened and empty.

Such mathematical precision and clarity is, of course, a hallmark of the early Italian Renaissance, where the treatises of Alberti and Brunelleschi emphasized the depiction of humanism through such vehicles. Why, then, is Grünewald’s humanism so markedly different from the Southern tradition? Why is there such an emphasis on corporal suffering and pain?

The altarpiece as andachtsbild

Such humanistic emphasis on the mortal form of Christ, especially on his emotional and physical pain, was a crucial part of the vibrant tradition of Northern Gothic and Renaissance spiritual art.

This emphasizing of the grief and suffering of holy figures in art, intended to facilitate a viscerally emotional connection between an artwork and its viewer, is a major linchpin in the Northern tradition of andachtsbilder, or “devotional images” in German. Andachtsbilder hyperfocused on sorrow; the grief of Christ in the artistic motifs of the Ecce homo, the Arma Christi, or the Pensive Christ, as well as the grief of his companions and friends in the motifs of the Mater Dolorosa and the Pietà, would have resonated with the Medieval and Renaissance-era faithful, especially in an age where death and suffering were not uncommon.

This relatively new tradition was a clear breakaway from the Medieval depictions of Christ when the Son of God was depicted as triumphant and simultaneously separated from the viewer. Artistic motifs such as the Christus triumphans and the common subject matter of the Last Judgement (especially popular in the tympana of cathedrals) emphasized the divinity of Christ, his holiness, and his lasting victory over sin and death. In Medieval works such as these, Christ’s face is one of transcendence and triumph.

This perspective of Christ as distant and victorious, however, started to shift in the early 13th century as part of a broader religious movement, which began to emphasize the humanity and sufferings of Christ, rather than his divine conquering, to pave an emotional connection between God and the common suffering of the average person. Starting from this time, influential writers such as Bonaventure and Meister Eckhart began to stress the humanity of Christ, and religious groups such as the Franciscans, the Beghards, and the Gottesfreunde followed. Indeed, as Dr. Nancy Ross says,

“Late medieval devotional writing… leaned toward mysticism and many of these writers had visions of Christ’s suffering. Francis of Assisi stressed Christ’s humanity and poverty. Several writers, such as St. Bonaventure, St. Bridget of Sweden, and St. Bernardino of Siena, imagined Mary’s thoughts as she held her dead son. It wasn’t long before artists began to visualize these new devotional trends” (Ross).

This vibrant and, from a modern point of view (one that has become admittedly tainted with a stereotypical perspective of the Middle Ages as a period of backwardness and fervently divine thought), surprisingly humanistic tradition extended throughout the 13th century and beyond with Thomas à Kempis’s The Imitation of Christ and the movement of the Devotio Moderna. Such theology had a humanistic bent to its core tenets and principles, emphasizing the spiritual connection between the divine and the mortal. These connections were made especially frequently through the use of compassion in pain; depictions of Christ and his followers in deep grief and emotional agony, although horrifically violent, were intended “to show that God and Mary, divine figures, were sympathetic to human suffering, and to the pain, and loss experienced by medieval viewers” (Ross).

An earlier artwork, similarly from the German andachtsbilder tradition, which we can compare to the Isenheim Altarpiece is the Röttgen Pietà. Here, the subject matter is a little different—the solitary Virgin Mary cradles the dead Christ after the Deposition—but the principal function of its form is remarkably similar. The Pietà, which would have been placed in a small chapel, aimed to elicit a similar emotional response and connection to the suffering of Christ. Similarly to the Isenheim Altarpiece, Christ’s wounds and form are exaggerated in their horrifying violence (his head bends backward at an unnatural angle, blood runs from his glaring stigmata, and his body and limbs are distorted to the point of near-abstractionism); the factor of physical pain is run to its absolute limit.

Emotional pain is dialed up as well. The face of the Virgin Mary is especially notable; holding her son’s body in her hands, her face is not one of quiet, accepting sadness or pensive tranquility (as is the case in Michelangelo’s rather more famous treatment of the same subject). Rather, she “appears to be angry and confused… She shows strong negative emotions that emphasize her humanity, just as the representation of Christ emphasizes his” (Ross).

Andachtsbilder such as these were meant to give a specific message, a specific kind of comfort and compassion, to their viewers. Medieval viewers, by seeing such gruesome pain experienced by even the divine, were meant to feel a closer, more personal connection to God, deeply intertwined with the emotional and the painful. “God sees and feels your pain,” the works say; “He suffered just as you did in life.”

Despair and triumph

Despite the emotional connection forged between the divine and the viewer through such themes of agony and suffering, though, the Isenheim Altarpiece is not entirely grounded on bodily pain. In fact, when the altarpiece was opened on special feast days, the viewers would have been greeted with a stunningly beautiful depiction of triumph over death, resurrection, and hope, a far cry from the subject matter of the front panels.

The inside panels depict what is essentially a speedrun through the life of Christ, depicting, from left to right, the Annunciation, the Nativity (angelic choir included), and a combination of Transfiguration, Resurrection, and Ascension.

This rightmost panel is especially fascinating and is described as “the strangest of these inner visions” (Hickson). Christ rises from the tomb and over the sleeping soldiers, wrapped in a brilliant cloak of bright yellows, oranges, reds, and blues. A shining body halo painted in sunset colors surrounds him, and his face, radiating with divine light, is so bright that it almost blends in with the halo behind his head. The scene is again during the night, but the subject matter is not death, but rather the triumph over death itself.

Christ’s body is again the center of our attention, but his body is perfect and otherworldly, unmarred by the scars of ergotism or pox. The wounds of his physical suffering, the stigmata, are transformed with a golden glow into a symbol of transcendence and triumph. His face is not contorted in pain, but tranquil in everlasting peace. This is a vibrant and physically moving depiction of Christ resurrected, of the divine victory over suffering and death. It certainly would have moved the patients of the Isenheim hospital, offering the hope of transcendence and peace to those afflicted with disease.

Grünewald has clear control of both the depiction of intense agony—both physical and emotional—and that of peaceful ascendancy. The Isenheim Altarpiece is simultaneously a praise of divine suffering, a sympathetic depiction of agony, and a prayer for hope after death. It is, in other words, a unique visual thesis on the nature of pain, faith, death, and resurrection.

Sources cited

Hickson, Sally. “Matthias Grünewald, Isenheim Altarpiece.” Smarthistory, 27 April 2023, https://smarthistory.org/grunewald-isenheim-altarpiece/.

Ross, Nancy. “Röttgen Pietà.” Smarthistory, 8 August 2015, https://smarthistory.org/roettgen-pieta/.

Hayum, Andrée. “The Meaning and Function of the Isenheim Altarpiece: The Hospital Context Revisited.” The Art Bulletin, December 1977, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3049705.

Stieglitz, Ann. “The Reproduction of Agony: Toward a Reception-History of Grünewald’s Isenheim Altar after the First World War.” Oxford Art Journal, 1989, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1360358?seq=5.

“The Isenheim Altarpiece animation.” YouTube, uploaded by Smarthistory, 18 April 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HoXwnbYR8Fk.